I can’t remember why I started drinking, even. I used to be able to remember. Then I forgot.

“You should see a therapist,” Janice told me. My sister.

“It’s not that big a problem,” I said. “Not yet.”

Janice grabbed my neck.

“Just go. It worked for Dad. And for Mom. Do you want to end up like Biscuit?”

I stared at the table.

I was pretty drunk.

We finished our drinks.

On the way out, I grabbed Janice’s neck. Or I would’ve fallen down.

I apologized.

“Thanks for breakfast,” she said.

Mom let me taste her margaritas. Growing up. Just one sip from each one. She could knock back quite a few.

“Doesn’t that taste awful?” she always said.

I always answered, “Yes.”

“So you’ll never drink them when you’re older?”

I always said “No.” Every time.

One night, coming back from a friend’s, I found my dad lying on his back on the lawn.

I helped him up. It was minus twenty.

“You forget how cold snow gets,” he said.

I helped him to the bedroom.

Mom was lying on the bedroom floor.

Biscuit and I picked her up and lay her on the bed next to Dad.

She opened her eyes for a second.

“Don’t tell my kids I was drinking,” she whispered.

Dr. Hollowood looked the part. He had hardly any hair, just a few scratches on the side. And glasses.

Though his office wasn’t like I’d pictured. There were no bookshelves or sumptuous carpets. There was no couch. There was a chair.

“Why do you drink?” he asked.

“I have no idea,” I said.

“Try to think.”

I thought as hard as I could. I was drunk.

“What are you thinking of?”

“What was the question again?”

We talked for maybe half an hour.

Dr. Hollowood looked at his watch.

“That’s all the time we have today. It’s my daughter’s wedding.”

I was wondering about the tux.

The saddest people in the world get together every morning. They wait in line for the liquor store to open.

I know most of them, though not really.

I was waiting in line.

The woman at the front of the line kept rubbing her face.

There was a young guy by the door. Sitting behind an empty guitar case. He didn’t have a guitar. I guess he was hoping for the best.

“It’s 10:01,” said the woman at the front, tapping on the glass.

The door opened.

On my way in, I tossed a quarter into the guitar case.

The guy looked up and smiled.

He still had a few good teeth.

Dr. Hollowood crossed his legs.

“Did you have a happy childhood?”

I knew he was going to say that.

“It was pretty happy, yeah.”

“You mentioned your parents were both alcoholics?”

“Yeah.”

“I guess I was happy anyway. I was a kid. It’s strange how that works.”

“How do you mean?”

“Well… You’re unhappy as a kid. But you’ll never be that happy again.”

Dr. Hollowood touched his chin.

The door opened. A man ran into the room.

“It happened again,” he said.

I met Janice for lunch.

It was May 23rd. I hoped she wouldn’t remember.

“You’re looking better,” she said.

“I’ve had maybe one or two drinks,” I said proudly.

I’d actually had three.

I hadn’t been that sober in a long time.

Janice looked wistful. She poked her spaghetti wistfully.

“You know, it’s been ten years.”

I knew she was going to say that.

“Hard to believe it. Ten years since—”

“I’ve gotta go,” I said, getting up. “See Dr. Hollowood.”

I grabbed my coat.

Janice rubbed my hand.

“Lunch is on me,” she said.

It was just about 10:00.

The woman at the front of the line was trying to rub her face off.

The guy behind the guitar case was sleeping.

The door opened.

When I got to the door, I stopped.

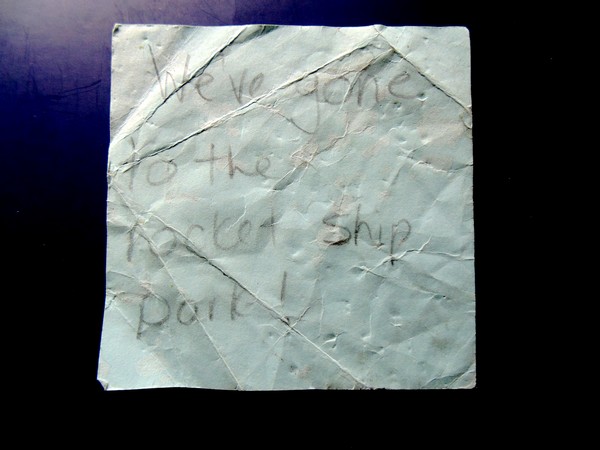

“I don’t want to do this anymore,” I said out loud.

I tossed two quarters into the guitar case.

The guy didn’t even wake up.

When I was seventeen and he was nineteen, my brother was driving us home from a party. We’d both been drinking. A car jumped over the median and hit us.

I remember … we were upside down.

I undid my seatbelt and fell down.

I undid Biscuit’s seatbelt and he fell down.

They think his neck was broken already.

Dr. Hollowood and I went golfing.

The first swing, I sliced pretty bad.

Dr. Hollowood lined himself up.

“It’s a matter of confidence,” he said. “Imagine the greatest golfer in the world. You’re him—only you’re better.”

He swung.

The ball landed right on the green.

I tried it. I imagined I was the best golfer in the world. I don’t really follow golf. I thought of Jack Nicklaus.

I hit the ball.

I hooked it, this time.

“Now you’re overconfident,” said Dr. Hollowood, laughing.

I lifted my club like I was going to smash it.

“You know what,” I said. “That’s it. Maybe that’s it. My drinking. My confidence. I basically have zero confidence.”

“Genetics is also a strong factor,” said Dr. Hollowood.

“You’re probably right,” I said.

I met Janice for dinner. It was my turn to pay—usually I’d pick someplace cheap—but I was saving so much by hardly drinking, I thought what the hell. We ate at Chez Pedro.

“You look great,” said Janice.

“I’m sober,” I said. I was.

A taco shouldn’t cost $30. I ate it slowly.

Janice stared at the table.

“I’ve got some flowers in the car,” she said. “You … want to come?”

“No,” I said. “I can’t deal with it.”

“No problem,” she said. “I understand.”

I stared at the table.

“What the hell,” I said, looking up. “Let’s go.”

Janice smiled.

There’s a ritzy cemetery downtown. Biscuit’s buried in the cemetery across from it.

Most of the headstones are pretty small and cheap. When I saw how shitty Biscuit’s looked in comparison—I’d never been there—my parents didn’t have a lot of money—I cried, just about. It was just an iron bar. The across part had fallen off.

Janice put the flowers down and cried.

I felt horrible. I needed a drink.

I hugged her.

It was bad.

It wasn’t that bad.

I saw Dr. Hollowood once a month. He recommended three times, but that’s a lot of money.

I had an appointment.

I was waiting to cross the street.

“Is my zipper open?” said the guy beside me.

It wasn’t.

He looked down.

“Is my dick out?”

I shook my head. A couple times.

He looked horrified.

“Then that means … I just pissed myself.”

I didn’t even laugh. It could’ve been me.

It was me. Just a few months ago.

I haven’t gotten drunk in a year. I haven’t had a drink in six months.

It’s not a long time.

It’s a long time.

One morning, walking past the liquor store, I was barely even tempted, I saw the guy with the case. He had a guitar now, too.

I’m not sure why. But I smiled.

♦

Rolli is a writer and cartoonist from Regina, SK, Canada. He’s the author of two short story collections (I Am Currently Working On a Novel and God’s Autobio), two books of poems (Mavor’s Bones and Plum Stuff), the middle grade story collection Dr. Franklin’s Staticy Cat and two forthcoming novels – Kabungo (Anansi/Groundwood, 2016) andThe Sea-Wave (Guernica Editions, 2016). As a creative columnist for The Walrus, Rolli publishes a new short story and cartoon every week at thewalrus.ca. His cartoons appear regularly in The Wall Street Journal, Reader’s Digest, Harvard Business Review, Adbusters and other popular outlets. Visit Rolli’s website and follow him on Twitter @rolliwrites.

♦♦♦