Phylo pastry…

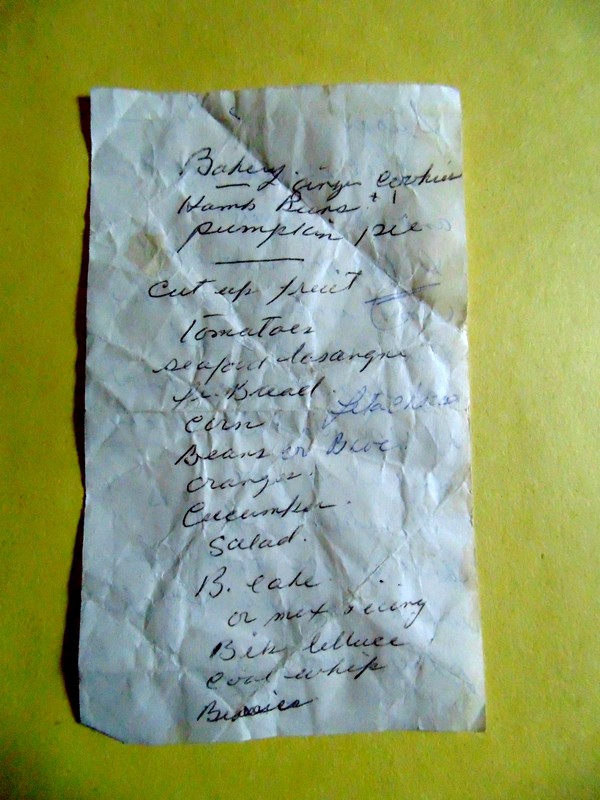

Written in a purposeful round hand; not the sort of hand that would lose the list before the shopping was complete; yet there the list lay on the pavement, trodden so many times the yellowish paper had the look of antique parchment.

…Phylo pastry

…Thyme

…Parsley

…Green onions…

A special dinner? An anniversary? Spanakopita as the starter, to set the atmosphere for the Greek Island cruise she plans to mention when he’s had a glass or two of wine?

Hang on. Shouldn’t retsina be on the list? Not to mention spinach for the pie! And doesn’t spanakopita need feta cheese? This is a disaster in the making. For a moment I can’t help looking around the Safeway lot for the figure I’ve dreamed up (pleated skirt, spectator pumps, blazer with a crest) to warn this woman of her lapse. Not that she’s the type to welcome that.

Instead, thanks to the “phylo” (far be it from me to challenge the woman on her spelling; she’s got problems enough) I find myself whisked back ten years to the seawall in West Vancouver on a blustery afternoon, and it is Dorothy Papadopoulos I encounter.

In the little Okanagan town where we grew up, Dorothy Papadopoulos was several grades ahead. I hardly knew her, except as the eldest of three beautiful sisters (the youngest was my classmate) who year after year were the acknowledged rulers of the popular kids, membership as unattainable for the likes of me as a trip to the moon. Thinking back, the Papadopoulos girls’ ascendency was a triumph. The valley’s original settlers were chiefly the sons of moneyed Brits, sent out to make their way by carving up the semi-desert into orchards, for recreation galloping over the hills — Tallyho! — hunting coyotes in place of foxes.

Popular. The word still brings an inner cringe. “Dear God please…” The pathetic nightly prayer.

Just before my mother died, on one of my visits home, she told me that Dorothy’s doctor husband had become head of anesthesiology at Vancouver General. So. Not only a doctor’s wife, but one who’d moved into a haute big-city echelon. In my teen years the still Brit-inflected wives of doctors, lawyers, bank managers, ruled our streets as effortlessly as the Papadopoulos sisters ruled the school. My mom was ironic about those contemporaries with their cut-glass smiles. But she was so encouraging and curious about the careers and adventures of my quasi peers as we all grew up, especially those who had moved on to a larger world, and she delighted in Dorothy’s visits to the studio. My mother’s own yearning for a larger world was something I never acknowledged as a youngster, or even as a teen. Where else should she be but making pots when she had a moment, and working alongside my dad in the orchard, and sewing clothes for me and for herself, and filling our house with flowers from the garden. For her, the prize-winning and the chance to travel came too late.

As Dorothy Papadopoulos approaches along the sea wall, her fine Greek profile carves the wind like a figure at the bow of a ship. She is wearing a belted camel coat, and enviable boots. I’m straight from my desk. Ink-stained hands and too tight jeans, the better to squeeze the words out. I sling my scarf around my neck, prepare to jog right by: not a chance that she’ll recognize me, anyway.

But her face breaks into a warm delighted smile. “Oh how wonderful…” Etcetera. “And you are so like your mother!”

She’s giving me a hug. There are tears in her eyes. It’s terrific to run into me. And how often she thinks of my mother! How she used to love visiting my parents’ studio, after her own mother died. “Your mother was always so welcoming. And I missed my own mother so! Those were the good years, weren’t they, growing up in our little town.” She dabs at her tears.

Bingo. Despite the intervening decades, I am back in the vice-grip of being a fourteen-year-old in that same small town, flushed with a germy memory. A moment when it seemed popularity might be on the doorstep after all.

But how unfair to pin the memory on Dorothy Papadopoulos — to hold back from the warmth of her greeting. Yes the Papadopoulos girls were the triumvirate at the top, but it wasn’t Dorothy or either of her sisters who stopped me in the school hallway one morning and invited me to join three of the cool girls at noon for a smoke break in a stolen car.

Joanie-who-shrank-her-sweaters-on-purpose invited me. She implied that this was a try-out, and if I passed I might be accepted into the group. I skipped French to go out and buy a pack of cork-tip Craven “A”. I didn’t know which cigarettes were cool.

Joanie had only been at our school a few months. She’d palled around with some of us lesser types at first, but it didn’t take her long to suss things out and make the necessary moves.

I never could figure out what those moves were — anymore than I could figure out why the Papadopoulos girls held sway, year after year. Their parents were from a foreign country just as mine were. Well my father was. And the war was well over by then. The fact that my family had been enemy aliens shouldn’t matter any longer. Besides, my mother wasn’t remotely German. My mother could trace her ancestry back to a signatory of the American Declaration of Independence. (When I mentioned that in class once, to prove my pioneer credentials, the teacher just rolled her eyes.)

Joanie.

And Linda-whose-father-was-on-the-School-Board. No teacher ever rolled eyes at her. Linda wore little white dickie collars with her appropriately loose sweaters, and spanking-clean saddle shoes.

And Eileen, the Royal-Bank-Manager’s-daughter. Eileen went out with Angelo who’d been suspended for coming to school with an Iroquois cut. It was Angelo who had hot-wired the car and parked it across the street from the school for us to smoke in.

If a Mountie came and caught us, Linda said, we could leave the situation to Joanie. “She knows all the cops in town.” Joanie ran her hands through her yellowy-white hair in an exaggerated Marilyn Monroe sort of way.

We all got out our smokes. Everyone helped themselves from my pack. I lit mine from the cork-tipped end.

I haven’t a clue what we talked about. I didn’t talk. It was all insider gossip, accompanying another round of my cigarettes.

Then Linda — “Oh oh!”

I ducked my head, peered out the rear window. The cops?

The others were opening their car doors — swinging them back and forth.

“Pee-yew…!”

“Who farted???”

They looked at me.

It had to be me, because it wasn’t any of them.

“My mother would kill me if I ever farted!”

“Mine too!”

“It’s eating cabbage that does it.”

“Yeah…!”

Thank goodness the bell rang then.

It was the bare-faced nature of the lies that obsessed me as I went back to class. All so prissy-perfect — My mother would kill me! — sending my single chance at popularity down the drain. And I hadn’t even smelled that fart. Nor did I get the cabbage reference till days later. It was years before it struck me that no one had farted. More years, before I figured out that the test had been for Joanie-the-sweater-shrinker. She’d been my friend, and if she wanted to move up into the clique she had to dump me for good, and prove it in some way. She’d dreamed the whole scheme up. That was why when I ran into her at a reunion years later (still sultry: but no more need to shrink her sweaters) she was so stand-offish, as if that fart still hovered in the air. Trying hard to blame the victim, still.

I’ve been nodding and smiling, and chiming in to Dorothy Papadopoulos’s reminiscences of growing up in our little town, while at the same time re-living that humiliation, which I haven’t thought of for years. Now she is looking at me curiously. Have I inadvertently wrinkled my nose at that ancient non-existent fart? I am ashamed of letting let my mind wander back to that petty event, when this woman is so clearly getting pleasure about sharing memories of times long past. Maybe a rare thing for any of us in our moving-around world.

How many of her city friends would have the faintest notion of our Main Street in those days: the Shell Station with its robot-looking gas pumps; the whiffy drafts from the fish shop, where the bodies on ice had come up over-night on the train; the grocery across the way with its oiled wooden floors and cheese in round wooden boxes that my dad used to take home and turn into stools. Across from the grocery was The Select Café and Bakery, which Dorothy’s family owned.

With a jolt, I realize that I knew practically nothing about her family as I was growing up, so deeply focused on my own outsider miseries: nothing except that they were Greek and owned that popular gathering-place, where black-clothed women worked at a table at the back making pastries and her mother was one of those.

The Papadopoulos sisters were so cool; they could do anything they wanted, that’s what I’d thought. Yet now Dorothy is telling me how strict her mother and grandmother had been, how the girls always had a curfew, how they were not allowed to attend Teen Town dances even, without their big brother going along to keep them safe. “We were so embarrassed.” She laughs. “I wish I had that kind of power over my own grandchildren!”

She and her sisters had envied me the freedom of growing up on a farm with artist parents, she says. “What a small place it was then! We knew everyone, didn’t we? I remember us sisters working in the café on Saturdays and your family would come in to do the shopping, in that terrific old Model T Ford. Your dad would park in front of the grocery. It was always a great moment when your mother stepped out of that old car looking so dashing, such a contrast, wearing bright lipstick and ultra stylish clothes…”

Such a contrast.

Again I stiffen. I was always proud of the way my mother managed to hold her head up, style-wise, when she dressed for town: outfits that came from pouring over Vogue pattern books, and hours at the treadle sewing machine. Was this an echoing snigger from those doctors’ wives in The Select for their morning coffee? “…And claiming fancy American ancestors, too! As if that cut any ice up here!”

But Dorothy is enthusing about how even in later years, even at her pottery wheel, my mother was a treat to see. On sunny days Dorothy would find her working out on the patio below the border of trailing petunias. Mom would immediately take off her canvas apron and she’d be wearing a boldly flowered shirt and slim boy’s pants and bright lipstick — and she’d bring out tea and home-made cookies, though she never ate any herself; she’d smoke a cigarette. (Another of those that killed her! That lovely patio scene zings straight into my heart.)

“She was so slim,” Dorothy is saying. “In my family food was such a lethally seductive form of love! All those delicacies made with phyllo pastry, by my mother and my aunties — basically just layer on layer of butter between sheets rolled as thin as gold leaf! Cream-filled bougatsa…” her face goes dreamy, “crunchy baklava … and little rolls filled with custard, I can’t remember the name …oh, and myzithropitakia…” lost completely for a moment in the memory of the sweet-cheese and honey pie she then describes. “All that was heaven when we were growing up, but (terrible to say) later us girls vowed we’d never put on weight they way our mom and aunties did. No wonder none of them lived to see their grand-kids!” She shakes her head. “But now I so regret never even learning how to make those wonderful dishes. Slimness isn’t everything, is it? What a sacrifice.”

“And I never learned to make pots.”

We stand and reminisce some more, old friends who never actually knew each other. And when we’ve finally parted, how strange to feel my heart puff with warmth: as if only now discovering what a long rise it has given to the curious confection that was life in my childhood town — sweet, sour, honeyed, crunchy, sometimes cruel — layer on layer of unexpected beauty, luck, regret.

♦

Barbara Lambert has won the Danuta Gleed Award for Best First Collection of Short Fiction and The Malahat Review Novella Prize, and been a finalist for the Ethel Wilson Prize and the Journey Prize. Her latest novel The Whirling Girl was published in the fall of 2012. Her previous work includes A Message for Mr. Lazarus (2000) and The Allegra Series (1999). Lambert is currently editor of Dr. Johnson’s Corner, an online gathering place for writers too in love with their own words. Barbara has lived in Vancouver, Ottawa, Barbados and Italy, and has now returned to her childhood home in the Okanagan Valley where she lives on a re-planted cherry orchard with her husband, Douglas.

She can be found at www.barbaralambert.com

♦♦♦

Up Next:

“Sitter

“Sitter

Skitter

Shitter”